by E. Wyn James

Who is the most famous Welshwoman in the world?

If you were to ask that question of passers-by shopping in Cardiff,

the Welsh capital, the answer would most likely be Shirley Bassey,

or Catherine Zeta Jones perhaps. That reply would be as good an

indicator as any of the seismic changes which have occurred in

Welsh culture over the past hundred years or so, because at the

end of the Victorian era ‘the most famous Welshwoman in

the world’ was one of the names given to the late eighteenth-century

hymn-writer, Ann Griffiths. One might well agree that Ann was

indeed the undisputed holder of that title in late Victorian times

were it not for one other candidate, a woman often referred to

by the Victorians and Edwardians as ‘the little Welsh girl

without a Bible’. That girl was Mary Jones, whose walk to

Bala in 1800 to buy a Bible has by today been retold in about

forty languages, and who can perhaps still be justifiably regarded

as the most famous Welshwoman in the world, as least in the realms

of international popular Christian culture.

Mary

Jones on her way to Bala in 1800

Three artist's impressions,

dating from the late nineteenth century, of Mary Jones on

her walk to Bala in 1800 to obtain a Bible from Thomas Charles |

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

(c) |

(a) From Robert Oliver Rees,

Mary Jones, Y Gymraes Fechan Heb yr Un Beibl ([1879]),

and subsequently included in M.E.Ropes, From the Beginning;

or, The Story of Mary Jones and Her Bible ([1882])

(b) From David Evans, The Sunday Schools of Wales ([1883]),

showing Cadair Idris in the background

(c) From John Morgan Jones and William Morgan, Y Tadau

Methodistaidd, vol. 2 (1897) |

Both women were relatively unknown until the 1860s,

in the case of Ann Griffiths, and the 1880s, in the case of Mary

Jones.1 However, by the end of

the nineteenth century both had become national icons, taking

their place beside two other Welsh ‘women’ who came

into prominence during that same period, namely ‘the Virtuous

Maid’ and the ‘Angel on the Hearth’.2

Indeed, it would not be far amiss to call Ann Griffiths and Mary

Jones the two most prominent female ‘saints’ of the

Liberal, Nonconformist Wales which came into being in the second

half of the nineteenth century. Our purpose here, however, is

not to discuss those romantic Victorian and Edwardian images,

but rather to consider Ann Griffiths and Mary Jones in their own

period and context, and especially as they relate to their great

mentor, Thomas Charles of Bala.

Ann and Mary: comparisons and contrasts

It is interesting to compare and contrast their lives. Both were

born in the last quarter of the eighteenth century – Ann

at the beginning of 1776 and Mary at the end of 1784. There was,

then, an age gap of only about nine years between them. This is

in stark contrast to their age at death. Mary’s life stretched

far into the nineteenth century. She died a blind widow in December

1864, having just reached her eightieth birthday. Ann Griffiths,

on the other hand, was a recently-married young woman when she

died aged 29 in August 1805, following the birth of her only child.

Both women lived in rural north Wales, and in

communities which were almost monoglot Welsh-speaking –

Mary in the parish of Llanfihangel-y-Pennant, fairly close to

the sea, in the north-western county of Merioneth; Ann in the

parish of Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa, fairly near the English border,

in the north-eastern county of Montgomery.3

The counties of Merioneth and Montgomery were the main centres

of the woollen industry in Wales from the middle of the sixteenth

century to the beginning of the nineteenth, and wool played a

prominent role in the lives of both Ann and Mary. Mary was the

daughter of weavers, and she and her husband, Thomas Jones, were

themselves weavers all their married life. Similarly, the handling

of wool was one of the main activities in Ann’s daily life.

Around the time of her death, there was a loom, five spinning

wheels and about eighty sheep on the family farm, Dolwar Fach.4

This throws into focus one major difference between

Ann and Mary. Mary had a very poor upbringing, raised by her widowed

mother in a small cottage. She was poor as a child and remained

poor to the grave. Ann on the other hand was reasonably well-off.

She was a farmer’s daughter. Although not rich, her father

was in a fairly easy financial position and played a prominent

role in local parish life; and when Ann married, she married into

a quite wealthy family. Her husband, Thomas Griffiths, brought

with him to Dolwar Fach, on his marriage to Ann, six silver spoons.

Until then, the kitchenware at Dolwar had been of pewter and wood,

with no silverware. From Elizabethan times onward a family’s

status depended on having at least six silver spoons, and it is

indicative that when the time came for Thomas Griffiths to leave

Dolwar Fach, following Ann’s death, he took the six spoons

with him.5

Thomas

and Sally Charles

Despite the difference in their social status,

Ann and Mary moved in the same social circles by virtue of the

fact that they were both Calvinistic Methodists. The great spiritual

awakening we refer to as the Methodist (or Evangelical) Revival

began in south Wales in the 1730s. Its development in north Wales

was initially fairly slow. Indeed it was not until the 1780s that

the Methodist movement began to gather strength in earnest in

north Wales, especially after an evangelical Anglican clergyman

from south Wales, Thomas Charles (1755–1814), moved to the

town of Bala, in central north Wales, and joined the Methodists

there.

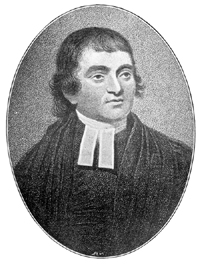

|

Thomas Charles

(1755-1814)

A portrait first published

in the Evangelical Magazine, September 1798 |

'The Lord’s gift to the North,’ is

how the pioneer Methodist leader and prince amongst preachers,

Daniel Rowland,6 described Thomas

Charles in 1785 – and not to north Wales alone by any means,

when one considers his significant contribution to the progress

of Christianity throughout Wales and beyond. But one should also

note the exceptional contribution made by his wife to Thomas Charles’s

achievements, for if there were ever an example of a wife playing

a key role in her husband’s success, Sarah Charles –

or Sally Charles as she is more frequently known – was that

person.

Sarah Charles (1753–1814) – Sarah

Jones before her marriage – came from Bala. She worked in

the family shop in that town. She was beautiful, intelligent,

very godly and had a fairly well-lined purse. The great Methodist

hymn-writer from south Wales, William Williams of Pantycelyn,7

was exceptionally fond of her, and it is said that he would have

liked her as a daughter-in-law. However, that was not to be. Thomas

Charles fell head over heels in love with her at first sight.

Their courtship was rather hesitant at first, from her side at

least, since she rather suspected Thomas Charles of having his

eye on her money. However, Charles proved an ardent and persistent

suitor, and after a long pursuit, he eventually married her.8

Sally Jones was determined to remain in Bala,

and Thomas Charles had no choice but to move there when they married

in 1783. Sally, then, was directly responsible for Thomas Charles

settling in Bala; and she and her shop were also responsible for

supporting him there, and providing the means by which he was

able to apply himself to his pioneer work among the Methodists

of north Wales. (It is worth noting in passing that the most prominent

Calvinistic Methodist leader of the next generation in north Wales,

John Elias of Anglesey, was also dependent on his wife’s

shop for his material support; similarly, his close colleague,

William Roberts of Amlwch was dependent on his wife’s shop,

as was Abraham Jones, the Methodist preacher of Llanfyllin, who

was supported in his work by the income from the shop of his wife,

Jane, the eldest sister of Ann Griffiths. Welsh Calvinistic Methodism

owes a great debt to shopkeeper wives!)

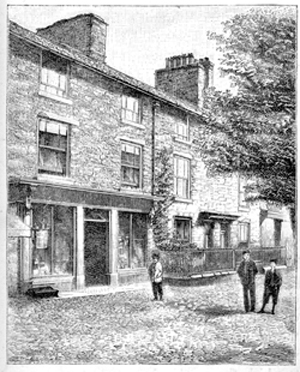

| |

|

|

Sally

Charles's shop in the High Street in Bala

From M.E.Ropes, From

the Beginning; or, The Story of Mary Jones and Her Bible

([1882])

In 1810 Sally Charles retired from the shop,

and she and Thomas Charles moved to the house next door,

on the right-hand side.

|

Thomas Charles: educator

One of Thomas Charles’s most important contributions was

his educational work. On moving north, he had been forcibly struck

by the spiritual darkness that surrounded him there. In order

to try and dispel that darkness, he decided to organise day-schools

on the pattern of the circulating schools of Griffith Jones of

Llanddowror – Charles, it should be remembered, was a native

of the Llanddowror area in southern Carmarthenshire. Griffith

Jones’s circulating schools had begun in the 1730s and had

proved a remarkable educational and religious experiment which

had succeeded in making the Welsh one of the most literate peoples

in Europe in the mid-eighteenth century.9

Griffith Jones’s schools had never been

as strong in north Wales as they had been in the South, and by

the time Charles moved to Bala they had all but disappeared. After

his removal to Bala, he began employing schoolmasters, arranging

for them to circulate from one neighbourhood to another, staying

in each place for a few months at a time in order to teach people

to read the Bible and to instruct them in the basic tenets of

the Christian faith. These peripatetic teachers proved to be exceptionally

effective missionaries, and their influence was to prove far-reaching.

In contrast to Griffith Jones, Thomas Charles, in addition to

organising circulating schools, also set up Sunday schools as

a channel for local people to continue the educational work after

the schoolmaster had moved to his next location. These circulating

schools and Sunday schools proved exceptionally successful, and

through them a large sector of the population of Wales became

literate.

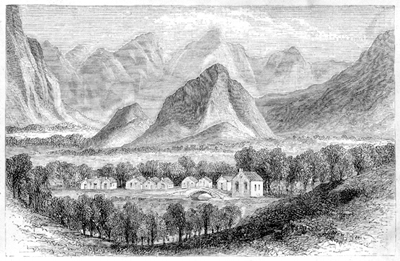

|

Llanycil Church

From John Morgan Jones and

William Morgan, Y Tadau Methodistaidd, vol. 2 (1897)

Bala was part of the parish of Llanycil until 1855. Llanycil

parish church is situated on the shores of Bala Lake about

one mile west of Bala. Thomas and Sally Charles were married

in Llanycil church in August 1783 and both were buried in

its churchyard in October 1814. |

Bala and revival

In tandem with Thomas Charles’s educational campaigns, north

Wales experienced in the same period a series of powerful spiritual

awakenings. One prominent authority on the history of Welsh revivals

has claimed that the years between 1785 and 1815 were, in his

opinion, the most successful period ever for religion in Wales.10

There is no better example of the striking spiritual

change wrought in that period than Bala itself. When the pioneer

Methodist evangelist, Howel Harris, visited the town during an

evangelistic preaching tour in 1741, he was almost killed by a

mob of fierce persecutors.11

Although he was accustomed to confrontation, Harris was so frightened

by the ferocity of the assault on him at Bala that he was unable

to face going anywhere near that town for many years to come.

However, a half century later, in 1791, the town of Bala was in

the grips of an extremely powerful religious awakening. Thomas

Charles says of one Sunday night in October 1791:

Towards the close of the evening service, the Spirit of God

seemed to work in a very powerful manner on the minds of great

numbers present, who never appeared before to seek the Lord’s

face [. . .] About nine or ten o’clock at night, there

was nothing to be heard from one end of the town to the other,

but the cries and groans of people in distress of soul.12

Many in north Wales embraced this fervent evangelical

Christianity in the years from about 1785 onward and a good number

of them joined the Calvinistic Methodists. By the beginning of

the nineteenth century, north Wales had become a stronghold of

Methodism, and Bala had become a veritable Jerusalem for the Methodists

of north Wales. This was partly due to its geographically central

location for the Methodists of the North; but above all, it was

the presence of Thomas Charles in the town which made it the hub

of the Methodist movement in north Wales.

|

Thomas Charles's

Communion Cup

Illustration by Rhiain M.

Davies

(first published in the Gregynog edition of the hymns and

letters of Ann Griffiths in 1998)

The silver cup used by Thomas Charles at

his monthly communion services in Bala is in the Calvinistic

Methodist Archives at the National Library of Wales.

|

A key factor in its prominence was the communion

services held by Thomas Charles at Bala on the last Sunday of

every month. Although the Welsh Calvinistic Methodists had, to

almost all intents and purposes, become a separate denomination

as the eighteenth century progressed, they did not formally secede

from the Anglican Church until they began ordaining their own

ministers in 1811. Prior to that only priests ordained by the

Anglican Church – the Established Church in Wales at that

time – were allowed to administer the sacraments among the

Welsh Methodists; and for about twenty years, from 1784 to 1803,

Thomas Charles was the only ordained priest ministering regularly

among the Methodists of north Wales.13

It is not surprising, then, that Methodists from far and wide

regularly attended the monthly communion services at Bala, not

to mention the great preaching festival linked to the Methodist

Association meetings held at Bala every summer.

Thirst for Bibles

As a result of Thomas Charles’s schools and the powerful

spiritual awakenings which interfaced with them, a substantial

sector of the population of Wales could not only read the Bible,

but also and more importantly, earnestly desired to read it. This

in turn created an enormous challenge for Thomas Charles, namely

how to satisfy the increasing demand for Bibles. It was the efforts

of Charles and others to ensure a regular supply of cheap Welsh

Bibles for the common people which led to the establishment of

the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1804. In a letter in

March 1804 to Joseph Tarn, another of the founders of the Bible

Society – a letter preserved in the Bible Society’s

archives in Cambridge University Library – Thomas Charles

gives some idea of the thirst for Bibles that characterised Wales

at that time:

The Sunday Schools have occasioned more calls for Bibles within

these five years in our poor country, than perhaps ever was

known before among our poor people [. . .] The possession of

a Bible produces a feeling among them which the possession of

no one thing in the world besides could produce [. . .] I have

seen some of them overcome with joy & burst into tears of

thankfulness on their obtaining possession of a Bible as their

own property & for their free use. Young females in service

have walked thirty miles to me with only the bare hopes of obtaining

a Bible each; & returned with more joy & thanksgiving

than if they had obtained great spoils. We who have half a doz.

Bibles by us, & are in circumstances to obtain as many more,

know but little of the value those put upon one, who before

were hardly permitted to look into a Bible once a week.

|

Testament

Newydd (1806)

The title page of the first

edition of the Welsh New Testament to be published by the

British and Foreign Bible Society. It was printed in Cambridge

in 1806. Ten thousand copies were published. They appeared

from the press in September 1806, and not May 1806 as stated

on the title page. |

It is not surprising that there was such a demand

for Bibles amongst the converts of the evangelical revivals of

the eighteenth century. The Bible was central to their lives.

For them, the Bible was the inspired and infallible word of God

and the final authority in all things pertaining to their faith

and life.

In 1792, when he was eighteen years of age, John

Elias ventured to the Methodist Association meetings in Bala with

a large group of young people who walked there from the Llŷn

Peninsula in western Caernarfonshire. The following extract from

his description of the journey to Bala clearly demonstrates the

importance of the Bible in the lives of these young Methodists:

We started on the journey, talking about the Bible and sermons.

Occasionally we sang psalms and hymns, and sometimes we rested,

and one or two would engage in prayer. Then we would proceed

again on our journey, singing on the way. Very few words were

uttered by any one among us all the way, except respecting the

Bible, sermons, and religious subjects.14

Rooted in Scripture

The Bible was central to Thomas Charles’s life and work.

Producing Bibles, winning readers to the Bible, expounding and

applying the Bible’s message – that was the very essence

of his work. To quote the late Professor R. Tudur Jones:

When we turn to Thomas Charles’s public work, it becomes

immediately obvious that his various projects all centre on

the Bible. He belonged to a generation of religious leaders

who shared the same ideals, and between them they were responsible

for weaving the Bible in a new way into the pattern of the life

and culture of the common people of Wales [. . .] He was intent

on building in Wales a civilization rooted in Scripture.15

|

Thomas Charles

Monument

From David Evans, The

Sunday Schools of Wales ([1883])

A marble monument to Thomas Charles –

the work of William Davies ('Mynorydd'; 1826-1901) –-

was erected in front of Capel Tegid, the Calvinistic Methodist

Chapel in Bala, in 1875. The seven-foot-high statue shows

Thomas Charles in a Geneva preaching gown, with one hand

on his heart and the other offering a copy of the Bible. |

After the Bible itself, and Thomas Charles’s

famous catechism, Hyfforddwr yn Egwyddorion y Grefydd Gristionogol

(‘Instructor in the Principles of the Christian Religion’),

which went to more than eighty editions in the nineteenth century,

possibly the most influential book in nineteenth-century Wales

was another work by Thomas Charles, his substantial Geiriadur

Ysgrythyrol (‘Scriptural Dictionary’). It was

written in order to help people better understand the Bible and

its teachings; and it is worth quoting (in translation) the opening

sentences of his introduction to that dictionary in order to demonstrate

the high esteem in which Charles held the Bible:

The Holy Scriptures are a treasure house of all profitable

and essential knowledge….. Since they have all been given

by the inspiration of God, they must partake of his perfection,

and befit it. Because of the perfection of his knowledge, he

cannot err; and because of the integrity of his nature, he will

not deceive us in any matter; therefore, the knowledge given

to us in the Scriptures is lofty, certain and complete. There

is nothing which pertains to our condition and our blessedness

in another world; nor anything which pertains to our circumstances

and our duties in this world, that God, in his holy word, has

not given us full instruction, how to behave in all things,

in all situations, and towards everyone. The great plan of salvation,

through a Mediator, shines clearly and fully in it, before a

world of sinners.16

|

Geiriadur

Ysgrythyrol (1805)

The title page of the first

edition of the first volume of Thomas Charles's famous Scriptural

Dictionary. The dictionary began appearing in parts from

about June 1802 onward. The final part of the first volume

appeared in November 1805, three months after Ann Griffiths's

death. It was to become one of the most influential books

in nineteenth-century Wales. |

With their leader holding the Scriptures in such

high regard, it is no surprise to see the Bible being afforded

a central place in the lives of that generation of Welsh Methodists

which grew up under Thomas Charles’s influence. Among them

were Ann Griffiths and Mary Jones, since both not only witnessed

the great evangelical revolution that swept north Wales during

their youth, but were also carried along by the spirit of that

revolution and into its epicentre.

Ann and Mary: pilgrims on the Bala way

Ann Griffiths and Mary Jones became Methodists in different ways.

Mary Jones’s parents were among the pioneer Methodists in

her area. From birth, then, she was part of that religious community.

She came to personal faith as a child of eight years, and was

accepted as a member of the local Methodist seiat (or

‘society meeting’) at that early age.17

About two years later, in 1795, Mary witnessed a period of significant

persecution of the Methodists of her area by a prominent local

landowner. Ann Griffiths would most certainly have sided with

the persecutors had she been living there at the time. Like most

Welsh people of the period Ann was a faithful Anglican. She would

tirade against all types of Nonconformist religion, and would

refer with derision to those going to the Methodist Association

meetings at Bala, ‘Look at the pilgrims going to Mecca.’

But in 1796, at about twenty years of age, Ann came under deep

conviction of sin, and would soon join the despised Methodist

seiat in her locality. Thereafter, she also would head

regularly for Bala, to the monthly communion services and the

annual Methodist Association meetings.

It was common at that time for Methodist maidservants

to include in their agreement of employment a clause which allowed

them to attend the Bala Association meetings every summer. In

return for that privilege they would take a reduction of five

shillings a year in their wages. It seems that such an arrangement

obtained in the case of Ruth Evans, who became maidservant at

Dolwar Fach in 1801, since there is mention of Ann offering Ruth

five shillings on one occasion so that she could go to Bala instead

of Ruth. However, by all accounts, Ruth preferred to go to the

Association meetings than accept the money!

|

Tŷ Uchaf,

Llanwddyn

Illustration by Rhiain M.

Davies

(first published in the Gregynog edition of the hymns and

letters of Ann Griffiths in 1998)

Ann Griffiths would often stay on Saturday

nights at Tŷ Uchaf, Llanwddyn, the home of a godly man

by the name of Humphrey Ellis, in order to break her journey

to Bala for Communion on Sunday mornings. |

Although Ann appears to have failed in her attempt

to attend the Association meetings on that occasion, in general

she seems to have succeeded in reaching Bala fairly regularly.

In his memoir of Ann Griffiths, published in 1865, Morris Davies

includes a number of anecdotes relating to a group of Methodists

from her area, and Ann prominent among them, who would cross over

the mountains to attend meetings at Bala. Returning home on Sunday

evenings, says one of her fellow-travellers, ‘our work along

the way was to listen to Ann Thomas reciting the sermons. I never

saw anyone like her for remembering.’ 18

The experience of going to Bala on Communion Sunday

and to the Association meetings was not unknown to Mary Jones

either. In old age, she would enjoy reminiscing of how in her

youth she would walk all Saturday night in order to reach Bala

in time for communion on Sunday morning, of the group prayer meetings

on the way, and of the powerful preaching and rejoicing she witnessed

in the open-air meetings on the Green in Bala.19

Members of the same community

It is quite probable that Ann and Mary, for a few years at the

beginning of the nineteenth century, actually attended the same

meetings at Bala, and knew one another – from a distance,

at least, across the crowds. In other words, they both belonged

to the same religious community, a community which centred on

Bala and on Thomas Charles. Indeed, all the elements which characterised

the Calvinistic Methodism of north Wales at the end of the eighteenth

century were at work in both their lives. Their spiritual experiences

were essentially the same, as were their beliefs. As regards religious

practise, they both spoke the same language, followed the same

customs, and attended the same type of meetings. They heard the

same preachers, read the same books, sang the same hymns. Both

knew Thomas Charles personally, and although Ann had not, like

Mary, been a pupil in one of Charles’s circulating schools,

both were deeply indebted to Thomas Charles’s educational

efforts. For example, the chief spiritual mentor in both cases

were teachers in Charles’s circulating schools: William

Hugh of Llanfihangel-y-Pennant in the case of Mary Jones, and

John Hughes of Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa (later of Pontrobert)

in that of Ann Griffiths.

One is very aware that, by placing Ann and Mary

side by side in this manner, one is in danger of giving the impression

that they were on a par. That is not the case. Both had strong

mental faculties, and both had extremely good memories, but Ann

was the genius. She was the born leader. Although a stanza reputed

to be the work of Mary Jones has survived in oral tradition, Ann

Griffiths had the richer cultural background and the poetic gifts.20

And while Mary Jones certainly had a vital spiritual experience

and a good grasp of the truths of Christianity, the more profound

spiritual experience and the more penetrating insights into those

truths belonged to Ann Griffiths.

Yet both were faithful and gifted disciples of

Thomas Charles and the Methodist movement to which they belonged.

That is nowhere to be see more clearly than in their strong emphasis

on the Bible; and in what follows we will look at the life of

each woman in turn, concentrating particularly on the predominant

role the Bible played in their lives.

Ann Griffiths

Ann Griffiths was born in 1776, the youngest but

one of the five children of John and Jane Thomas of Dolwar Fach

farm in the parish of Llanfihangel-yng-Ngwynfa, Montgomeryshire.

Her two sisters had left home by the time their mother died in

1794, leaving Ann at 17 years of age the mistress of the house;

and she would remain mistress of Dolwar until her own early death

in 1805.

|

Ann Griffiths

(1776-1805)

From David Thomas, Ann

Griffiths a'i Theulu (1963)

There are no pictures of Ann Griffiths.

This effigy, based on contemporary descriptions, is in the

Ann Griffiths Memorial Chapel at Dolanog, a village near

her home. The chapel was opened in July 1904. |

Ann received a religious upbringing. Her father

was more zealous than was the norm among Anglicans. He attended

services regularly at his parish church and held family devotions

at home every morning and evening. According to tradition a remarkable

old dog at Dolwar would follow its master to Llanfihangel Parish

Church every Sunday morning, lying quietly under the pew until

the service was over; and a sign of Ann’s father’s

regularity at the morning service is that the dog would attend

every Sunday morning through force of habit, even if no member

of the Dolwar family were present! Yet despite the family being,

by all accounts, sincere and conscientious Anglicans, almost each

of them in turn came to the conviction that they did not possess

true experiential faith: four of the five children experienced

conversion as adults, and their father also followed the same

spiritual path before his death. They all joined the Welsh Calvinistic

Methodists, and Dolwar Fach became a preaching station for the

Methodists for some years.

Although they would no doubt have described their

religion before turning to the Methodists as being ‘superficial’,

and although they would have received as much pleasure, to say

the least, in joining in the dancing and the evening entertainment

and the Sunday afternoon sports as they did in the Sunday morning

services in the parish church, their regular attendance at Church

services and their custom of holding daily devotions on the hearth

meant that the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer were part of

their staple diet. They were also raised in the sound of the traditional

Welsh Christmas carols – known as plygain carols21

– which were full of biblical allusions and are often described

as sermons in song; and it is possible to see hints of the influence

of the Book of Common Prayer and the plygain carols on

Ann’s work, the fruit of her Anglican upbringing.

Biblical immersion

As has already been emphasised, in joining the Methodists, Ann

was joining a people for whom being immersed in the Bible was

a matter of great importance. They read the Bible regularly; they

studied it ardently, every part of it; they meditated upon it

and learned substantial portions by heart. The Bible penetrated

the very marrow of their being, controlling their mind and actions

and colouring their language, both oral and written.

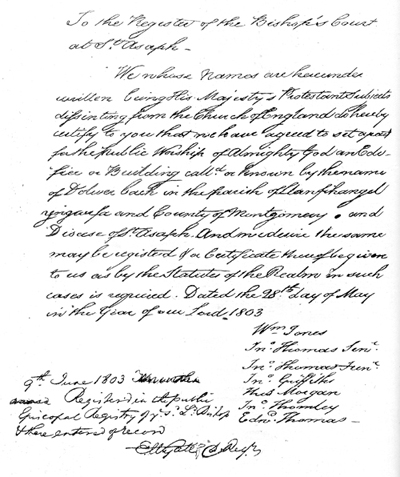

|

Dolwar Fach's

Registration Licence for Public Worship (1803)

Reproduced in Cymru,

January 1906

In May 1803 Ann Griffiths's father, John

Thomas, and her two brothers, John and Edward, were among

those who signed an application to the Bishops's Court at

St Asaph for their home, Dolwar Fach, to be registered as

a place for worship. |

The following description by a woman who was well

acquainted with the Dolwar family, clearly demonstrates the central

place Ann afforded the Bible in her life following her conversion:

There would be a very pleasant appearance to the family at

Dolwar while spinning, with the old man [Ann’s father]

carding wool, and singing carols and hymns. At other times,

a solemn silence would reign among them. Ann would spin with

her Bible open in front of her in a convenient place, so she

could snatch up a verse while carrying on with her task, without

losing time. I saw her at the spinning wheel in deep meditation,

paying heed to hardly anything around her, and the tears flowing

down her cheeks many times.22

Why the central role afforded to Scripture in

Ann’s life? The simple answer, as has already been suggested,

is because she was convinced that the Bible was the Word of God

and the only sure and sufficient guide for her life.

Biblical experience

One of the most notable aspects of Ann Griffiths’s life

is the deep spiritual experiences which characterised it, experiences

which resulted in her rolling on the floor on occasions and going

into a deep trance-like meditation at other times. She herself

states in a letter to one of her Methodist friends, Elizabeth

Evans, that she would sometimes become so absorbed in spiritual

matters that she would completely fail ‘to stand in the

way of my duty with regard to temporal things’. In such

a state, she says, ‘the Lord sometimes reveals through a

glass, darkly, as much of his glory as my weak faculties can bear’.23

It was deep spiritual experiences such as these that led Thomas

Charles to declare during a visit to Dolwar Fach that he was of

the opinion that Ann ‘was very likely to meet with one of

three things – either that she would meet severe trials;

or that her life was almost at an end; or else that she would

backslide’.24

Ann termed such periods of spiritual absorption

‘visitations’. A real danger facing anyone receiving

such profound spiritual ‘visitations’ as these is

to be ruled by those feelings and experiences. Not so in Ann’s

case. There is in her life and work a remarkable balance between

the subjective and the objective, between clarity of mind and

intensity of experience. She fears ‘imaginations’

(as she calls them) above all else, almost, and welcomes the authority

of the Bible – an objective and final authority outside

of herself – to control those imaginations. ‘I am

constrained to be grateful for the Word in its invincible authority,’

she says in a letter to her mentor, John Hughes, Pontrobert, in

1802.25

It is important to emphasise that the Bible did

not play a merely negative role in Ann’s life and spiritual

experience. It is true that the Bible prevented her from believing

certain things, that it forbade her from acting in certain ways,

and kept a reign on her spiritual experiences in certain directions.

But the Bible also played a positive role in such matters. As

regards spiritual experiences, for example, the Bible was a means

of creating and deepening her experiences, as well as directing

and controlling them. In her letters, almost every other sentence

contains a reference to some Scriptural verse or other which had

been impressing itself on her mind, enlightening her, comforting

or chastening her. Indeed, one of her great fears was that she

would fail ‘to find her condition in the Word’. The

Bible, then, was the interpreter and nurturer of her spiritual

experience. Indeed, it would not be an overstatement to claim

that it was not her own subjective fancies, but rather biblical

revelation, which fashioned the nature of her experience of the

Godhead.

|

The Old Chapel,

Pontrobert

Illustration by Rhiain M.

Davies

(first published in the Gregynog edition of the hymns and

letters of Ann Griffiths in 1998)

Ann Griffiths was a member of the Calvinistic

Methodist seiat ('society' or 'fellowship meeting')

which met chiefly at Pontrobert. She worshipped regularly

in the cahpel which was erected in Pontrobert in 1800 to

house the seiat. |

Biblical language

In her hymns and letters, Ann Griffiths expresses her beliefs

and experience in biblical terms. Although one can hear a hint

of her Montgomeryshire Welsh dialect at times in her work, that

is not the language Ann uses in composing her hymns and letters,

but rather a more formal Welsh which we may term ‘the language

of the seiat’ or ‘the language of the pulpit’

– similar in register to the language used by her great

Methodist forerunner, William Williams of Pantycelyn, in his hymns

and prose, and based to a large degree on the language of the

Bible. The Bible was also the ultimate source of her imagery,

although much of that imagery was in widespread circulation both

in the speech of her fellow Methodists at Pontrobert and indeed

throughout Wales, being part of what one Welsh literary critic

has called the ‘common currency of the hymn’s literary

style’.26 Ann, then, utilised

in her compositions both the linguistic and the literary conventions

of the religious community to which she belonged – conventions

that were Wales-wide and Bible-centred.

Welsh hymn-writers of the eighteenth-century evangelical

awakenings breathe the atmosphere of the Bible. Their work abounds

in words and imagery which emanate from Scripture. Likewise Ann.

In general, she uses the same biblical imagery as the other hymn-writers

and draws heaviest on the same sections of the Bible as they do

– in particular, the prophecy of Isaiah, the Song of Solomon

and the Psalms in the Old Testament, and the epistle to the Hebrews,

the book of Revelation and the Gospels in the New Testament. Yet

Ann’s use of the Bible is more intense and more exclusive

than that of the others. For example, William Williams of Pantycelyn

remains, to some degree at least, a nature poet of this world

in his hymns; not so Ann Griffiths. In her work, every

plant is a heavenly one, and every mountain is in the

Middle East. In general, also, Ann Griffiths’s hymns are

a tighter weaving of scriptural allusions than those of the other

hymn-writers. The scriptural references and allusions are, in

the main, more condensed and complex than in the work of the others.

One literary critic has graphically described the process Ann

uses in her hymns as that of making a collage of biblical

pictures, ‘bringing together various experiences and names-for-experiences

into a new, wondrous unity’.27

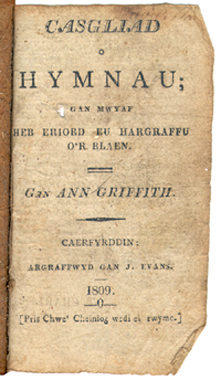

|

|

Casgliad

o Hymnau (1809)

The title page and preface

(by Thomas Charles) of the 1809 edition of the collection

of hymns in which Ann Griffiths's work was first published.Tthe

first edition was printed in Bala in 1806. The 1809 edition,

printed in Carmarthen, has the distinction of being the

earliest edition of the collection to include Ann's name

on the title page. It is one of the earliest examples in

Welsh of a woman's name being included on the title page

of a printed volume. |

Ann Griffiths’s copious scriptural references

underline the breadth of her knowledge of the Bible and her great

debt to it as a source of ideas and imagery; but those extensive

biblical references have led to the accusation that she does little

more in her work than string together biblical texts. This does

her a great disservice, since Ann clearly selects her biblical

references with much skill and deftness, and at her best she succeeds

in creating out of them stanzas which are ‘rounded, finished

and majestic compositions’.28

These biblical references enrich her work greatly, both on a literary

and a spiritual level. As Professor R. M. (Bobi) Jones has emphasised,

they perform a role similar to Classical references in other types

of poetry.29

Unfortunately, the abysmal ignorance of the Bible

which characterises contemporary Welsh life and culture, results

in the loss to the contemporary reader of much of the wealth of

meaning in Ann’s work. It also leads to much misunderstanding

and misinterpretation of her work. For example, it has been fashionable

to discuss the ‘erotic element’ in the work of Ann

Griffiths, and to quote in that context a line from the end of

perhaps her greatest hymn, ‘Cusanu’r Mab i dragwyddoldeb’

(‘Kissing the Son for eternity’), without realising

that Ann Griffiths had Psalm 2:12 in mind – ‘Kiss

the Son, lest he be angry’ – and that the kiss in

question is one of homage to a king.

One further aspect of her use of the Bible should

be emphasised, namely that she views the Bible, not as a collection

of independent books, but as a single composition, with one divine

Author and one basic message running through the whole. One result

of this is that she draws, in her work, on almost every book of

the Bible, those of the Old Testament as well as the New, and

interweaves references to them comprehensively. Another point

that should be noted is that she is thoroughly Christocentric

in her interpretation of the Bible. Christ is the key to the whole;

to Him everything refers, sometimes clearly, at other times in

parables and types. Ann Griffiths would certainly have agreed

wholeheartedly with William Williams of Pantycelyn when he wrote

in his epic poem, Golwg ar Deyrnas Crist (‘A Prospect

of the Kingdom of Christ’): ‘My Jesus is the marrow

of the Bible, there is not a chapter which does not speak, indirectly

or directly, of a crucified Lamb.’30

Mary Jones

In turning to Mary Jones the first point that

needs to be underlined is the prominent place afforded to the

Bible throughout her long life. As has already been noted, Mary

was born in December 1784, the daughter of poor weavers, Jacob

and Mary Jones, who lived in a cottage called Ty'n-y-ddôl

in the parish of Llanfihangel-y-Pennant at the foot of one of

the highest mountains in Wales, Cadair Idris. To the best of our

knowledge, she was their only child. Her father died in March

1789 when Mary was just over four years of age, and she and her

mother faced much hardship in the years that followed. These were

years which saw a significant increase in poverty in rural Wales

in general as a result of the incessant warring between Britain

and France following the French Revolution, together with other

economic factors.

|

Mary Jones Monument

Photograph: Bible Society

(reproduced in Elisabeth Williams, To Bala for a Bible,

in 1988)

This monument to Mary Jones was erected

in 1907 in the ruins of Tyn-y-ddôl, the cottage in

Llanfihangel-y-Pennant where she and her mother were living

in 1800, at the time of Mary's walk to Bala to obtain a

Bible from Thomas Charles. |

Mary received a Methodist upbringing, very different

from that of the majority of her contemporaries, which would have

been characterised by superstition and levity. This did not mean,

of course, that her upbringing was dull and tedious and lacking

in joy. As one prominent critic of the literature of eighteenth-century

Welsh Methodism has emphasised on more than one occasion: ‘Methodism

organised different types of enjoyment for its adherents.’31

It is worth quoting here part of a letter sent by Thomas Charles

to Sally Jones on 1 March 1780, which emphasises the nature of

the Christian’s enjoyment in this life:

There can be no happiness but in ye enjoyment of ye inexhaustible

and overflowing source of all goodness and perfection. As we

lost our happiness by separating ourselves from God, so ye only

way of regaining it is, by returning to him again; for he has

promised to meet us in Christ and there (and no

where else) to be forever reconciled to us. But

notwithstanding, Creatures, not ‘as they are

subject to vanity’, but as Creatures of God can,

and do contribute much to our happiness by

his (observe) blessing. God has diffused himself

thro’ all his creatures, and when we enjoy him in

his creatures, then they answer to us the end for which they

were created. So that the love of God and of his creatures not

only are consistent, but inseparably connected together.32

It has already been noted that Mary came to personal faith at

eight years of age, and was received into membership of the local

Methodist seiat at that time, sometime in 1793. It was

unusual in that period for children to become seiat members

at such an early age, but since Mary attended other religious

meetings of an evening with her widowed mother, in order to carry

the lamp for her, she was also allowed to accompany her mother

to the seiat meetings. Early in life, then, she became

very familiar with the content and message of the Bible –

much more familiar than most children in her area at that time.

When Mary Jones was about ten years of age, one

of Thomas Charles’s circulating schoolmasters, a man called

John Ellis, came to keep day-school at Abergynolwyn, some two

miles from Mary’s home; and before long a Sunday school

was also established there. By all accounts, one of the most punctual

and regular attendees at both these schools (to the extent that

her circumstances allowed) was Mary Jones. She earnestly sought

scriptural knowledge, and it is obvious from the surviving evidence

that she was a capable pupil, with a very good memory –

indeed, in old age she could still recite faultlessly large portions

of Thomas Charles’s catechism, the Hyfforddwr (‘Instructor’).

Her biographer, Robert Oliver Rees, says of her: ‘She distinguished

herself especially in the Sunday school by treasuring in her memory,

and reciting aloud in public, entire chapters of the Word of God,

and in her “good understanding” of it.’33

|

Hyfforddwr

yn Egwyddorion y Grefydd Gristionogol (1807)

The title page of Thomas

Charles's famous catechism, first published in 1807. It

went to more than eighty editions during the nineteenth

century. An English translation was published in 1867 under

the title, The Christian Instructor; or Catechism on

the Principles of the Christian Religion. |

To Bala for a Bible

Apart from the copy of the Bible in the parish church, the only

Bible in the vicinity at that time, it would seem, was the one

at Penybryniau Mawr, a farmhouse about two miles from Mary’s

home.34 The Bible was kept on

a table in the small parlour, and Mary was given permission by

the farmer’s wife to go and read it, on condition that she

removed her clogs before venturing in. It is said that Mary would

walk there every week, whatever the weather, over a period of

some six years in all, to read the Bible and commit portions to

memory.

However, her great desire was to obtain a Bible

of her own. The story of her walk to Bala, barefoot for most of

the way, in order to purchase a Bible from Thomas Charles, is

well-known in Christian circles world-wide. That was in 1800,

when she was fifteen years old. It would have been a round journey

of about fifty miles. However, the heroic effort on her part was

not so much in walking to Bala as in the sacrifice and perseverance

involved in saving to buy a Bible. Walking that sort of distance

to Bala was not at all unusual among Methodists of the period,

and walking barefoot was quite normal among the common people

at that time; but for someone as poor as Mary Jones, saving enough

money to buy a Bible was a great sacrifice. Bibles were very expensive

in those days, and she would have had to have scrimped and saved

every penny for years before succeeding to accumulate the little

over seventeen shillings she would have needed to buy a Bible

– a huge sum for a poor girl like Mary.

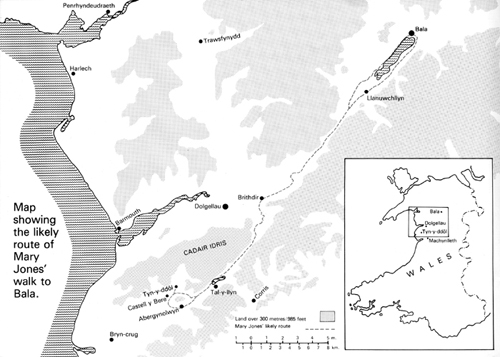

|

Map showing

the likely route of Mary Jones's walk to Bala in 1800

Map by Christine James

(based in part on an article by Donald Hoare in Country

Quest, May 1968

and first published in Elisabeth Williams, To Bala for

a Bible, in 1988) |

A few years ago a stanza was published which had

been preserved in oral tradition over several generations in the

Llanfihangel-y-Pennant area. It is said to have been composed

by Mary Jones herself, and although I am far from convinced of

this, it is intriguing that the first person listed in the chain

of people who had a hand in its preservation in oral tradition

was someone from Penybryniau Mawr, the farm to which Mary is said

to have gone regularly to read the Bible. Here is the stanza in

English translation:

Yes, at last I have a Bible,

Homeward now I needs must go;

Every soul in Llanfihangel

I will teach its truths to know;

In its dear treasured pages

Love of God for man I see;

What a joy in my own Bible

To read of His great love for me.35

Mary Jones and the Bible Society

It is said that Mary Jones’s visit to Thomas Charles in

1800 to purchase a Bible made such an impression upon him that

he had no peace of mind until he had found a way to ensure a regular

supply of cheap Bibles for the common people of Wales. Furthermore,

according to tradition, Charles’s telling of the story of

Mary’s visit to him had such an electrifying effect on the

members of committee of the Religious Tract Society at their meeting

in London at the end of 1802, that they began to seek in earnest

the possibility of founding a society to publish and distribute

Bibles, not only for Wales, but also for the whole world.

|

Old Swan Stairs,

near London Bridge

From William Canton, The

Story of the Bible Society (1904)

The counting-house of the prosperous merchant,

Joseph Hardcastle, by the Old Swan Stairs, where the committee

meeting of the Religious Tract Society was held on 7 December

1802, which Thomas Charles attended and in which the formation

of the British and Foreign Bible Society was proposed.

|

It was this which led to the formation of the

British and Foreign Bible Society in 1804, a matter of great joy

to Thomas Charles, Ann Griffiths and Mary Jones. As Thomas Charles

said in a letter in July 1810:

I was continually applied to for Bibles, & much distressed

I was (more than I can express) to be forever obliged to say,

I could not relieve them. The institution of the British &

Foreign B[ible] S[ociety] will be to me, & thousand others

cause of unspeakable comfort & joy as long as I live. The

beneficial effects already produced in our poor country, of

the abundant supply of Bibles by the means of it, are incalculable.36

Some have questioned the role played by Mary Jones

in the history of the founding of the Bible Society. The most

vociferous among these was probably the colourful bibliophile,

Bob Owen of Croesor. ‘It is a great shame’, he once

said, referring to a monument erected in the ruins of Mary Jones’s

cottage in Llanfihangel-y-Pennant, ‘that the meagre pennies

of the quarrymen, miners and farmers were spent raising a monument

to one who had nothing to do with the founding of the Bible Society.’37

It is true that there is no contemporary evidence

that Thomas Charles told the story of Mary Jones’s walk

to Bala at the committee meeting in London at the end of 1802;

and one should certainly not over-emphasize Mary Jones’s

part in these matters. Thomas Charles would certainly have known

of many other examples of the great thirsting after the Bible

that characterised so many of the common people of Wales in his

day. And yet, from a fairly early period, there is regular mention

that one girl had made a particular impression on Thomas Charles;

and all the evidence suggests that Mary Jones was that person,

and that a special rapport had developed between her and Thomas

Charles following her visit to Bala to purchase a Bible.

For example, when special meetings began to be

held for Thomas Charles’s Sunday schools, where the pupils

from a number of schools would come together to be publicly examined,

Mary Jones would attend such meetings in her area as faithfully

as she possibly could; and she would by all accounts excel in

them. In a manuscript lodged at the National Library of Wales

in Aberystwyth, Robert Griffith, Bryn-crug (a minister who knew

Mary well towards the end of her life), said that her answers

‘would descend in showers like balls of fire’, with

great effect on the gathered crowd. Robert Griffith adds that

Thomas Charles would be certain to ask every time he came to a

meeting of schools in the vicinity of her home, ‘Where is

the weaver [i.e. Mary Jones] today, I wonder?’ Robert Griffith

also tells how Mary would often meet Thomas Charles at Methodist

Association meetings and converse with him on such occasions.

Bees and Bibles

Mary Jones had a long life. It was a poor and a grim one in many

ways. She married in 1813. At least six children were born to

her and her husband, but most of them died young. Only one child

seems to have survived her, and he had by then emigrated to the

United States. Around 1820, Mary and her husband, Thomas, moved

a few miles nearer the coast, to the village of Bryn-crug near

Tywyn, and it was there that she spent the remainder of her days,

dying in 1864, an aged and blind widow.

|

Bryn-crug

From M.E. Ropes, From

the Beginning; or, The Story of Mary Jones and Her Bible

([1882])

Mary Jones spent most of her adult life

in Bryn-crug, a village a few miles from the sea, near Tywyn,

Meirioneth. She is buried in the graveyard of the Calvinistic

Methodist Chapel at Bryn-crug, where she was a faithful

member. |

Yet despite all her hardships and troubles, and

although she suffered much from depression in later years, her

Christian faith held to the end, and she was noted for her faithfulness

to the Calvinistic Methodist cause in Bryn-crug. Despite her poverty,

she contributed regularly to the work of the Bible Society, and

donated half a sovereign to the special collection made in 1854

to send a million New Testaments to China, to celebrate the fiftieth

anniversary of the founding of the British and Foreign Bible Society.

Part of Mary Jones’s income came from keeping

bees. It is not impossible that Thomas Charles was a help to her

in that respect also! His scriptural dictionary is a treasure-trove

of information on all manner of subjects, including bees and honey.

Keeping bees was a common practise at that time. There were six

beehives at Dolwar Fach, for example; and it is quite possible

that they (together with Psalm 118:12) were in Ann Griffiths’s

mind when she composed the words:

Weary is my life, by foemen

Thick beset in savage throng,

For like bees they come about me,

Harass me the whole day long . . .38

But the imagery of bees as enemies is not appropriate

in Mary Jones’s case. Here again (in translation) are the

words of Robert Griffith, Bryn-crug:

She [i.e. Mary Jones] had only a small garden of land, and

that was very full of fruit, and a myriad of bees, and she would

be like a princess on a fine summer’s day, in their midst,

and she could pick them up in her hands like corn, or oatmeal,

without any one of them using its sting to oppose her.

She kept the income from selling the honey for

her own livelihood, but she divided the income from the beeswax

– which could be a considerable sum – between the

Bible Society and her denomination’s Missionary Society;

and she attributed the fact that the bees did not sting her, and

that they were so productive, and that their produce was of such

high quality, to the fact that they knew that Mary dedicated a

substantial portion of that produce to the work of their Creator.

The section of the Trysorfa (‘Treasury’),

her denominational magazine, to which Mary Jones would always

turn first was the ‘Missionary Chronicle’. The same

missionary interest is evident in Ann Griffiths. She has a hymn

on the theme of the success of overseas mission, and it is worth

remembering that John Davies, one of Thomas Charles’s circulating

school teachers, and a member of the same Methodist seiat

as Ann, sailed as a missionary to Tahiti in 1800.39

Thomas Charles could well have been the source of the interest

of both Ann and Mary in the mission field. He laid great emphasis

on overseas missionary work.40 He says, for example, in the letter

to Joseph Tarn in March 1804, which has already been quoted:

These noblest institutions, the Missionary [Society, i.e. the

London Missionary Society, formed in 1795, of which Charles

was a director], the Sunday School, together with the Bible

Society added now to the other two, compleat the means for the

dispersion of divine knowledge far & near.

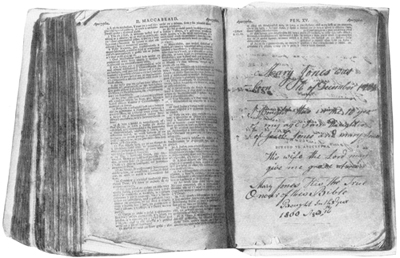

|

Mary Jones's

Bible

Mary Jones's own Bible,

which she obtained from Thomas Charles in Bala in 1800,

is now kept in the British and Foreign Bible Society's Archives

in Cambridge University Library. It is a copy of the 1799

edition of the Welsh Bible, ten thousand copies of which

were printed at Oxford for the SPCK. In addition to the

Old and New Testaments and the Apocrypha, the volume contains

the Book of Common Prayer (in Welsh) and Edmwnd Prys's Welsh

metrical versions of the Psalms. Mary Jones wrote the following

(in English) on the last page of the Apocrypha:

Mary Jones was born 16th of December 1784.

I Bought this in the 16th year of my age. I am Daughter

of Jacob Jones and Mary Jones His wife. the Lord may give

me grace. Amen.

Mary Jones His The True Onour of thie Bible. Bought In the

Year 1800 Aged 16th. |

In her old age, Mary Jones would enjoy telling

the tale of her walk to Bala to obtain a Bible. She made good

use of the Bible she received from Thomas Charles. She read it

from cover to cover four times during her lifetime. She memorised

substantial sections of it, which proved of great benefit and

comfort to her after she lost her sight. And when she died, the

Bible she had bought in Bala over sixty years previously was on

the table by her side.

* * *

One of the best-known stanzas in popular Welsh

hymnody is ‘Dyma Feibl annwyl Iesu’ (‘This

is Jesu’s dear Bible’). Its authorship is given as

‘anonymous’. As the Welsh poet, Menna Elfyn, has reminded

us in one of her poems, where she plays on the prefix ‘an-’

and the name ‘Ann’, ‘anonymous’ can often

mean that a work was composed by a woman. Although not certain,

the likelihood in this particular case is that the stanza was

actually composed by a man. His name was Richard Davies, a native

of Tywyn in Merioneth, who was born in 1793 and served as a Calvinistic

Methodist elder there until his death aged 33. The stanza first

appeared in print, to the best of our knowledge, in a collection

of hymns published by one Thomas Owen in Llanfyllin, a market

town in Montgomeryshire, in 1820.

The reason for mentioning this is that the stanza

binds Ann Griffiths and Mary Jones together in more ways than

one. Richard Davies, like both Ann and Mary, was a Calvinistic

Methodist. Tywyn, where he lived, is but a stone’s throw

from Mary Jones’s home, and she would certainly have known

him. Llanfyllin, the place the stanza was first published, is

only a stone’s throw from Ann Griffiths’s home. Ann

Griffiths and Richard Davies both died young; indeed, Ann was

in her grave before Richard composed his stanza. However, had

she lived, it would not be difficult to imagine her and Mary Jones

singing together that simple but catholic stanza with fervour

on the Green in Bala during a Methodist Association meeting. Here,

then, to close is that stanza in translation:

This is Jesu’s dear Bible,

Precious gift of God’s right hand;

There we find the rule for living

And the path to Canaan’s land;

There we read our ruin’s story,

Eden’s sad and sorry loss;

There we find the way to glory

Through my Jesus and His cross.41

Notes

1 ‘Ann Griffiths’

was Ann’s married name; her maiden name was ‘Ann Thomas’,

although she would have been commonly known as ‘Nansi Thomas’.

‘Mary Jones’ was both Mary’s maiden name and

her married name, although she would have been generally known

as ‘Mari Jacob’ – Jacob being her father’s

first name.

2 See, for example, Sian Rhiannon

Williams, ‘ The True “Cymraes”: Images of Women

in Women’s Nineteenth-Century Welsh Periodicals’,

in Angela John (ed.), Our Mothers’ Land: Chapters in

Welsh Women’s History, 1830–1939 (Cardiff: University

of Wales Press, 1991), chapter 3. See also my Welsh-language articles,

'Ann Griffiths: O Lafar i Lyfr', in Chwileniwm: Technoleg

a Llenyddiaeth, ed. Angharad Price (Cardiff: University of

Wales Press, 2002), pp. 54-85, and ' "Eneiniad Ann a John":

Ann Griffiths, John Hughes a Seiat Pontrobert', Transactions

of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 10 (2004), pp.

111-32.

3 By coincidence the parish churches

of both women were dedicated to St Michael (the Archangel), hence

the ‘Llanfihangel’ in the names of both their parishes.

‘Llan’ is a Welsh word for ‘church’, while

‘Fihangel’ is a mutated form of ‘Mihangel’,

the Welsh form of ‘Michael’.

4 Helen Ramage, ‘Y Cefndir

Cymdeithasol’, in Y Ferch o Ddolwar Fach, ed. Dyfnallt

Morgan (Caernarfon: Gwasg Gwynedd, 1977), p. 11.

5 Helen Ramage, ‘Crandrwydd

y Perlau Mân’, Y Casglwr, 24 (Christmas 1984),

p. 14.

6 On Daniel Rowland, and his influence

on Thomas Charles, see Eifion Evans, Daniel Rowland and the

Great Evangelical Awakening in Wales (Edinburgh: Banner of

Truth Trust, 1985).

7 For good English introductions

to William Williams of Pantycelyn, see Glyn Tegai Hughes, Williams

Pantycelyn, ‘Writers of Wales’ series (Cardiff:

University of Wales Press, 1983); Eifion Evans, Pursued by

God: A Selective Translation with Notes of the Welsh Religious

Classic, Theomemphus, by William Williams of Pantycelyn (Bridgend:

Evangelical Press of Wales, 1996). On his debt to Jonathan Edwards,

see R. Geraint Gruffydd, ‘The Revival of 1762 and William

Williams of Pantycelyn’, in Emyr Roberts and R. Geraint

Gruffydd, Revival and Its Fruit (Bridgend: Evangelical

Library of Wales, 1981). I provide a short, popular introduction

in my article ‘William Williams: The Sweet Singer of Wales’,

Evangelical Times, 25:4 (April 1991), p. 7.

8 See R. Tudur Jones’s published

lecture, Thomas Charles o’r Bala: Gwas y Gair a Chyfaill

Cenedl (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1979), pp. 17-20;

this Welsh-language book is the best short introduction to Thomas

Charles and his work. In English, see Iain H. Murray, ‘Biographical

Introduction’, in Edward Morgan, Thomas Charles’

Spiritual Counsels (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1993).

Gwen Emyr tells the story of Thomas and Sally’s romance

in her Welsh-language volume, Sally Jones: Rhodd Duw i Charles

(Bridgend: Evangelical Press of Wales, 1996). For a detailed account

of their relationship, including substantial selections of their

voluminous correspondence, see the exhaustive three-volume biography

by D. E. Jenkins, The Life of the Rev. Thomas Charles

(Denbigh: Llewelyn Jenkins, 1908; second edition, 1910).

9 On Griffith Jones and his circulating

schools, see Glanmor Williams, Religion, Language and Nationality

in Wales (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1979), chapter

9, and (in Welsh), Gwyn Davies, Griffith Jones, Llanddowror:

Athro Cenedl (Bridgend: Evangelical Press of Wales, 1984).

On his piety, see Eifion Evans, Fire in the Thatch: The True

Nature of Religious Revival (Bridgend: Evangelical Press

of Wales, 1996), chapter 4. I discuss his attitude to the Welsh

language in my chapter, ‘ “The New Birth of a People”:

Welsh Language and Identity and the Welsh Methodists, c.1740–1820’,

in Religion and National Identity: Wales and Scotland c.1700–2000,

ed. Robert Pope (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2001). See

also R. M. Jones and Gwyn Davies, The Christian Heritage of

Welsh Education (Bridgend: Evangelical Press of Wales, 1986).

10 Henry Hughes, Bryncir, Hanes

Diwygiadau Crefyddol Cymru (Caernarfon: Cwmni’r Wasg

Genedlaethol Gymreig, [1906]), p. 170; see also D. Geraint Jones,

Favoured with Frequent Revivals: Revivals in Wales 1762–1862

(Cardiff: Heath Christian Trust, 2001).

11 William Williams, Swansea,

Welsh Calvinistic Methodism, third edition, ed. Gwyn

Davies (Bridgend: Bryntirion Press, 1998), pp. 91–3. On

Howel Harris, see Geoffrey F. Nuttall, Howel Harris, 1714–1773:

The Last Enthusiast (Cardiff: University of Wales Press,

1965); Eifion Evans, Howel Harris, Evangelist (Cardiff:

University of Wales Press, 1974); Geraint Tudur, Howell Harris:

From Conversion to Separation, 1735–1750 (Cardiff:

University of Wales Press, 2000).

12 D. E. Jenkins, The Life

of the Rev. Thomas Charles, vol. 2, p. 89.

13 D. E. Jenkins, The Life

of the Rev. Thomas Charles, vol. 3, pp. 239-40.

14 Edward Morgan, John Elias:

Life, Letters and Essays (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust,

1973), p. 16.

15 R. Tudur Jones, Thomas

Charles o’r Bala: Gwas y Gair a Chyfaill, pp. 21, 38

(my translation).

16 Geiriadur Ysgrythyrol,

vol. 1 (Bala: R. Saunderson, 1805). The dictionary went into eight

editions in the nineteenth century, not to mention American editions

for the Welsh-speaking communities of North America.

17 On the seiat, the

local fellowship meetings which were a key element in Welsh Calvinistic

Methodism, see Eifion Evans, Fire in the Thatch, chapter

7, and the English translation by Bethan Lloyd-Jones of William

Williams of Pantycelyn’s classic 1777 work on the subject,

The Experience Meeting – An Introduction to the Welsh

Societies of the Evangelical Awakening (Bridgend: Evangelical

Movement of Wales, 1973; new edition, Vancouver: Regent College

Pub., 2003). The Welsh word seiat derives from the English

‘society’.

18 Morris Davies, Cofiant

Ann Griffiths (Denbigh: Thomas Gee, 1865), p. 44 (my translation).

19 Descriptions of Mary Jones

in old age, and her reminiscences of her famous walk to Bala,

are to be found in K. Monica Davies, ‘Mary Jones (1784–1864)’,

Journal of the Historical Society of the Presbyterian Church

of Wales, 52:3 (October, 1967), pp. 74–80; see also

Roger Steer, Good News for the World: The Story of Bible Society

(Oxford: Monarch Books, 2004).

20 See my article, 'Ann Griffiths:

Y Cefndir Barddol', Llên Cymru, 23 (2000), pp.

147-70. I provide a general introduction to her life and work

in English on the Ann Griffiths Website – www.anngriffiths.cf.ac.uk.

21 The Welsh word ‘plygain’

comes from the Latin, ‘pullicantio’ (‘cock crow’),

and refers to a service with carols traditionally held early on

Christmas morning.

22 Morris Davies, Cofiant

Ann Griffiths, pp. 39–40 (my translation).

23 H. A. Hodges’s translation

of the letter in A. M. Allchin, Songs To Her God: Spirituality

of Ann Griffiths (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cowley Publications,

1987), p. 96. H. A. Hodges’s English translations of Ann

Griffiths’s letters and hymns are also to be found on the

Ann Griffiths Website – www.anngriffiths.cf.ac.uk).

24 Morris Davies, Cofiant

Ann Griffiths, p. 60 (my translation).

25 H. A. Hodges’s translation

in A. M. Allchin, Songs To Her God, p. 89.

26 T. J. Morgan, ‘Iaith

Ffigurol Emynau Pantycelyn’, in Ysgrifau Beirniadol

VI, ed. J. E. Caerwyn Williams (Denbigh: Gwasg Gee, 1971),

p. 111 (my translation).

27 Derec Llwyd Morgan, ‘Emynau’r

Cariad Tragwyddol’, Barddas, 94 (February, 1985),

p. 6 (my translation).

28 J. R. Jones, ‘Ann Griffiths’,

Llên Cymru, 8:1–2 (1964), p. 34 (my translation).

29 Bobi Jones (ed.), Pedwar

Emynydd (Llandybïe: Llyfrau’r Dryw, 1970), pp.

13–16. See also his article, ‘Another Celtic Spirituality

– The Calvinistic Mysticism of Ann Griffiths (1776–1805)’,

Foundations, 38 (Spring, 1997), pp. 39–44; 39 (Autumn,

1997), pp. 31–6.

30 Gomer M. Roberts (ed.), Gweithiau

William Williams, Pantycelyn, vol. 1 (Cardiff: University

of Wales Press, 1964), p. 121 (my translation). On Williams Pantycelyn’s

epic, Golwg ar Deyrnas Crist, see Glyn Tegai Hughes,

Williams Pantycelyn, pp. 10–22.

31 Derec Llwyd Morgan, Pobl

Pantycelyn (Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer, 1986), p. 96; cf. pp.

66–8. His important work on early Welsh Methodist literature,

Y Diwygiad Mawr (Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer, 1981), has been

translated into English by Dyfnallt Morgan, The Great Awakening

in Wales (London: Epworth Press, 1988).

32 D. E. Jenkins, The Life

of the Rev. Thomas Charles, vol. 1, pp. 156–7.

33 Robert Oliver Jones, Mary

Jones, Y Gymraes Fechan heb yr Un Beibl, new edition (Wrexham:

Hughes and Son, 1903), p. 15 (my translation).

34 That copy of the Bible is

still extant. Some pages are reproduced in Elisabeth Williams,

To Bala for a Bible (Bridgend: Evangelical Press of Wales,

1988), p. 7.

35 Translated from the Welsh

original in Elisabeth Williams, To Bala for a Bible,

p. 11.

36 Cambridge University Library,

Bible Society’s Collections, BSA/D2/1/3.

37 University of Wales Bangor

MS 2384 (my translation); see also Dyfed Evans, Bywyd Bob

Owen (Caernarfon: Gwasg Gwynedd, 1977), pp. 224-5. On Bob

Owen (Robert Owen, 1885–1962), see the Dictionary of

Welsh Biography 1941–1970 (London: Honourable Society

of Cymmrodorion, 2001) – also available in electronic form

on the National Library of Wales website (http://yba.llgc.org.uk/).

38 H. A. Hodges’s translation

in A. M. Allchin, Songs To Her God, p. 108.

39 On John Davies (1772–1855),

see Eifion Evans, Fire in the Thatch, chapter 11.

40 See my Welsh-language articles,

'Williams Pantycelyn a Gwawr y Mudiad Cenhadol', in Cof Cenedl

XVII, ed. Geraint H. Jenkins (Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer,

2002), pp. 65-101, and 'Pererinion ar y Ffordd: Thomas Charles

ac Ann Griffiths', Cylchgrawn Hanes (Historical Society

of the Presbyterian Church of Wales), 29-30 (2005-06), pp. 73-96.

41 Translated from the Welsh

original in Elisabeth Williams, To Bala for a Bible,

p. 17.

[This article first appeared in the Autumn 2005 issue of Eusebeia:

The Bulletin of the Jonathan Edwards Centre for Reformed Spirituality

(published under the auspices of Toronto Baptist Seminary). It

is a revised version of a Welsh-language article which appeared

under the title ‘Ann Griffiths, Mary Jones a Mecca’r

Methodistiaid’ in Llên Cymru, 21 (1998),

a journal published by the University of Wales Press. ]